Technical Ingredient Overview

🏭 Manufacturer — (not specified)

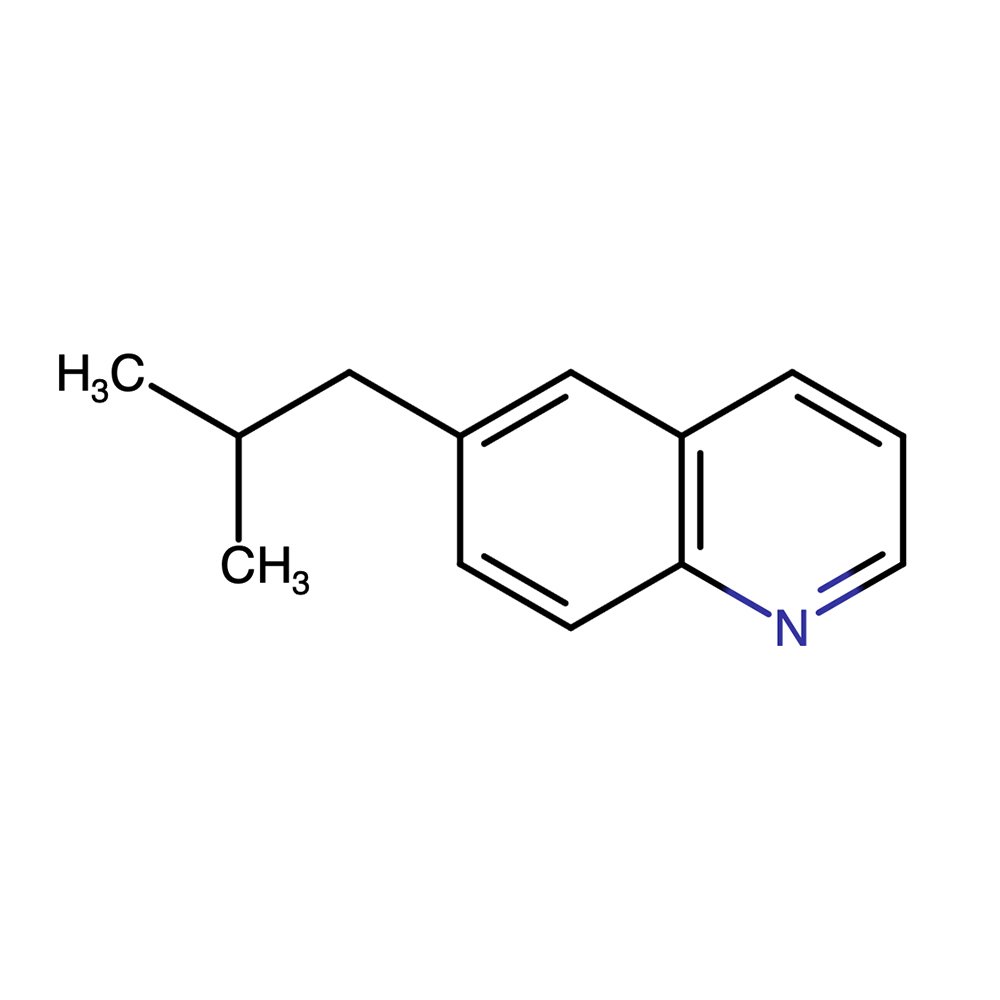

🔎 Chemical Name — 6-Isobutylquinoline

🧪 Synonyms — IBQ; 6-(2-Methylpropyl)quinoline

🧬 Chemical Formula — C13H15N

📂 CAS — 68198-80-1

📘 FEMA — Not listed

⚖️ MW — 185.26 g/mol

📝 Odor Type — Leather, animalic, woody

📈 Odor Strength — Very strong

👃🏼 Odor Profile — Dry, leathery, warm, tobacco-like, ink-like, with animalic and woody nuances

⚗️ Uses — Fine fragrance (leather, tobacco, fougère, and woody accords), aroma enhancement

🧴 Appearance — Pale yellow to amber liquid

What is 6-Isobutyl Quinoline?

6-Isobutyl Quinoline (IBQ) is a nitrogen-containing heterocyclic aromatic compound used in perfumery primarily for its intense, leathery-animalic scent. Belonging to the family of alkyl-substituted quinolines, it is structurally characterized by an isobutyl group attached to the sixth position of the quinoline ring. The compound is not naturally occurring and is synthesized for use in fine fragrance formulations, especially to evoke notes associated with aged leather, tobacco, or animalic warmth.

Historical Background

The synthetic quinoline family found its way into perfumery in the early 20th century as chemists began exploring nitrogen heterocycles for their robust olfactory effects. The most historically significant derivative, ethyl quinoline, appeared in the late 19th century and was soon followed by numerous alkyl-substituted variations. 6-Isobutyl Quinoline emerged as a particularly potent and versatile leather note enhancer. Although the exact date and origin of its first synthesis in perfumery are not clearly documented, it was extensively studied and catalogued in technical compendia such as Arctander's Perfume and Flavor Chemicals and by researchers examining quinoline derivatives for their fixative and character-enhancing qualities (Arctander, 1969; Surburg & Panten, 2016).

Olfactory Profile

Scent Family: Leathery / Animalic / Woody

6-Isobutyl Quinoline is renowned for its powerful, tenacious, and extremely diffusive scent that mimics the rich complexity of tanned leather, warm tobacco, mossy woods, and animalic ink-like tones. It serves both as a primary character molecule and a background enhancer, delivering profound depth even at trace levels.

Intensity: Very strong and long-lasting

Volatility: Low (high substantivity)

Fixative Role: Excellent, particularly in leathery or tobacco-themed accords

Applications in Fine Fragrance

IBQ is a staple in masculine compositions, leather accords, chypres, and fougères, where it evokes naturalistic impressions of aged leather, dry woods, or even ink and smoke. It blends harmoniously with birch tar, castoreum bases, vetiver, patchouli, oakmoss, and aldehydic green notes, and is commonly used in:

Leather and suede-inspired fragrances

Tobacco-based compositions (e.g., pipe tobacco, cigar blends)

Fougere bases to bring a nostalgic, vintage masculinity

Animalic or ink-like niche perfumes with artistic profiles

Notable Use Cases: Though often used in trace amounts due to its potency, 6-Isobutyl Quinoline can be found in modern reimaginations of classic leather fragrances and avant-garde niche perfumes that explore abstract themes such as "library," "old books," or "skin."

Performance in Formula

Diffusion: Excellent; even in small dosages (often <1%), it radiates clearly

Stability: Highly stable in both alcoholic and oil-based systems

Compatibility: Broad compatibility across musky, woody, green, and balsamic bases

Impact: High; can overwhelm a formula if not dosed with precision

Industrial & Technical Uses

While its primary application remains in fine perfumery, 6-Isobutyl Quinoline has seen limited interest in flavor research(non-FEMA listed) and functional perfumery (e.g., leathery or musky nuances in detergents and air care), though rarely used due to its cost and strength. Its odor type makes it unsuitable for most food or cosmetic applications beyond luxury perfumery.

Regulatory & Safety Overview

IFRA: As of the 51st Amendment, 6-Isobutyl Quinoline is restricted in use based on its potential for sensitization and its structural similarity to other nitrogen heterocycles under scrutiny. Its maximum permitted levels depend on the product category (consult IFRA Standard).

GHS Classification: Not classified under most systems but may cause skin sensitization in certain individuals.

EU Cosmetics Regulation: Not included on the Annex II list (substances prohibited in cosmetics), but precaution is advised due to sensitization potential.

REACH: Registered under EU REACH regulation; not classified as SVHC

FEMA: Not listed as GRAS or approved for use in food

Proper safety protocols including protective gloves and ventilation are recommended during handling due to potential dermal and respiratory sensitization.

Additional Information

Storage: Should be stored in tightly sealed containers, away from light and air, at room temperature or below, to prevent degradation.

Stability: Excellent shelf-life when stored correctly; color may deepen slightly with age without affecting olfactory performance.

References

Arctander, S. (1969). Perfume and Flavor Chemicals (Vol. II). Montclair, NJ: Author.

Surburg, H., & Panten, J. (2016). Common Fragrance and Flavor Materials: Preparation, Properties and Uses (6th ed.). Wiley-VCH.

PubChem. (2024). 6-Isobutylquinoline. Retrieved from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/68198-80-1

IFRA. (2023). IFRA Standards – 51st Amendment. International Fragrance Association. Retrieved from https://ifrafragrance.org